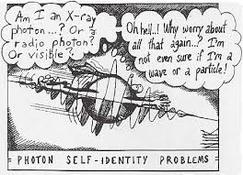

Quantum reality doesn't exist until we're looking at it........ Oh really? That's the view of most physicists these days. Until something is being observed, it doesn't exist, and the observer, it would seem, has to conform to certain constants and constraints before becoming adept/conscious/sentient enough to qualify as an observer. Such as being - a person, maybe? Or something with a brain? Something like us, surely, some higher form of life to look down on the lowly nanoscopic world and be able to judge whether a table is one or not. Long ago there was a famous quantum question posed in bars and cafes - if a tree falls in the forest when no-one is there, does it make any sound? This soon became outdated when quantum questions posed by the likes of Schroedinger's cat came into public view, and right now public view seems wide open to the possibility that quantum physics has something important to say, at some point in time. Reading Quantum by Manjit Kumar, I'm tracing the trail of quantum realisation through the stories of all the famous scientists in the early 1900s who collaborated to create what became known as 'quantum mechanics'. It's abundantly clear that getting hung up on the math was a good thing, for without their devotion to the equation none of the properties of quanta would have been realised. But when we come down to the argument between Heisenberg and Schroedinger over wave-particle duality and uncertainty, you can get the distinct feeling that someone's missing something here. Okay, an electron (or photon, or quark, or anything else small enough to qualify as the bedrock of reality) is both particle and wave at the same time, so it's placement in space (position) can't be ascertained at the same time as the speed it's travelling at (velocity) because the math doesn't let one be known at the same time as the other. The scientists scurried back to laboratories and libraries to argue the toss between theory and experiment, but as Schroedinger's cat is about to step into/out of the box (which is about where I'm at in the book) they've just dumped matrix mathematics (which is apparently extremely complicated) in favour of Schroedinger's simpler wave equations when computing what atoms and their components do. Is it a wave or a particle and when is it one or the other and how can that be?  Maybe the answer to that is really, really easy. Maybe wave is the formation everything takes until the moment of realisation when its a particle. That means that we are all waves just a nanosecond ago and in a nanosecond from now there's every likelihood your wave will become particles again but depending where you are in the room or the forest or the bath, your position will have changed slightly and so all the bits that make you up become particles in that space you then occupy. A little like being in a permanent Star Trek transporter beam you don't actually know you're in. We therefore wander about as waves thinking we are particles all the time, because the only time we are particle in nature is in the Now. This has nothing to do with our observation per se, but everything to do with the big question of who observes what. Einstein grumbled in 1924, "I find the idea quite intolerable that an electron exposed to radiation should choose of its own free will, not only the moment to jump off [its energy level in the atom], but also its direction. In that case, I would rather be a cobbler..." Double slit would seem to suggest that quantum particles do indeed make decisions, based on factors we can't possibly determine unless we were to be in there in that field with them. But just as we don't know we're waves because to all outer appearances we are particles, there's no reason to suggest even the most intellectual electron is any better off than we are.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorKathy is the author of Quantumology. She met up with quantum mechanics in 1997, pledging allegiance to its sources thereafter. These are her personal thoughts and testimonies. Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed